How Images Think: A Review

SOME COMMENTS ON HOW IMAGES THINK

Some years ago, I wrote a book with the rather provocative title, How Images Think. The book sold well and is still available. Professor Pramod Nayar of the University of Hyderabad wrote this excellent review in the Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. Here are some selections. The full review is available at the Journal website.

How Images Think is an exercise both in philosophical meditation and critical theorizing about media, images, affects, and cognition. Burnett combines the insights of neuroscience with theories of cognition and the computer sciences. He argues that contemporary metaphors - biological or mechanical - about either cognition, images, or computer intelligence severely limit our understanding of the image. He suggests in his introduction that image refers to the complex set of interactions that constitute everyday life in image-worlds (p. xviii). For Burnett the fact that increasing amounts of intelligence are being programmed into technologies and devices that use images as their main form of interaction and communication - computers, for instance - suggests that images are interfaces, structuring interaction, people, and the environment they share. New technologies are not simply extensions of human abilities and needs - they literally enlarge cultural and social preconceptions of the relationship between body and mind.

The flow of information today is part of a continuum, with exceptional events standing as punctuation marks. This flow connects a variety of sources, some of which are continuous - available 24 hours - or live and radically alters issues of memory and history. Television and the Internet, notes Burnett, are not simply a simulated world - they are the world, and the distinctions between natural and non-natural have disappeared. Increasingly, we immerse ourselves in the image, as if we are there. We rarely become conscious of the fact that we are watching images of events - for all perceptive, cognitive, and interpretive purposes, the image is the event for us.

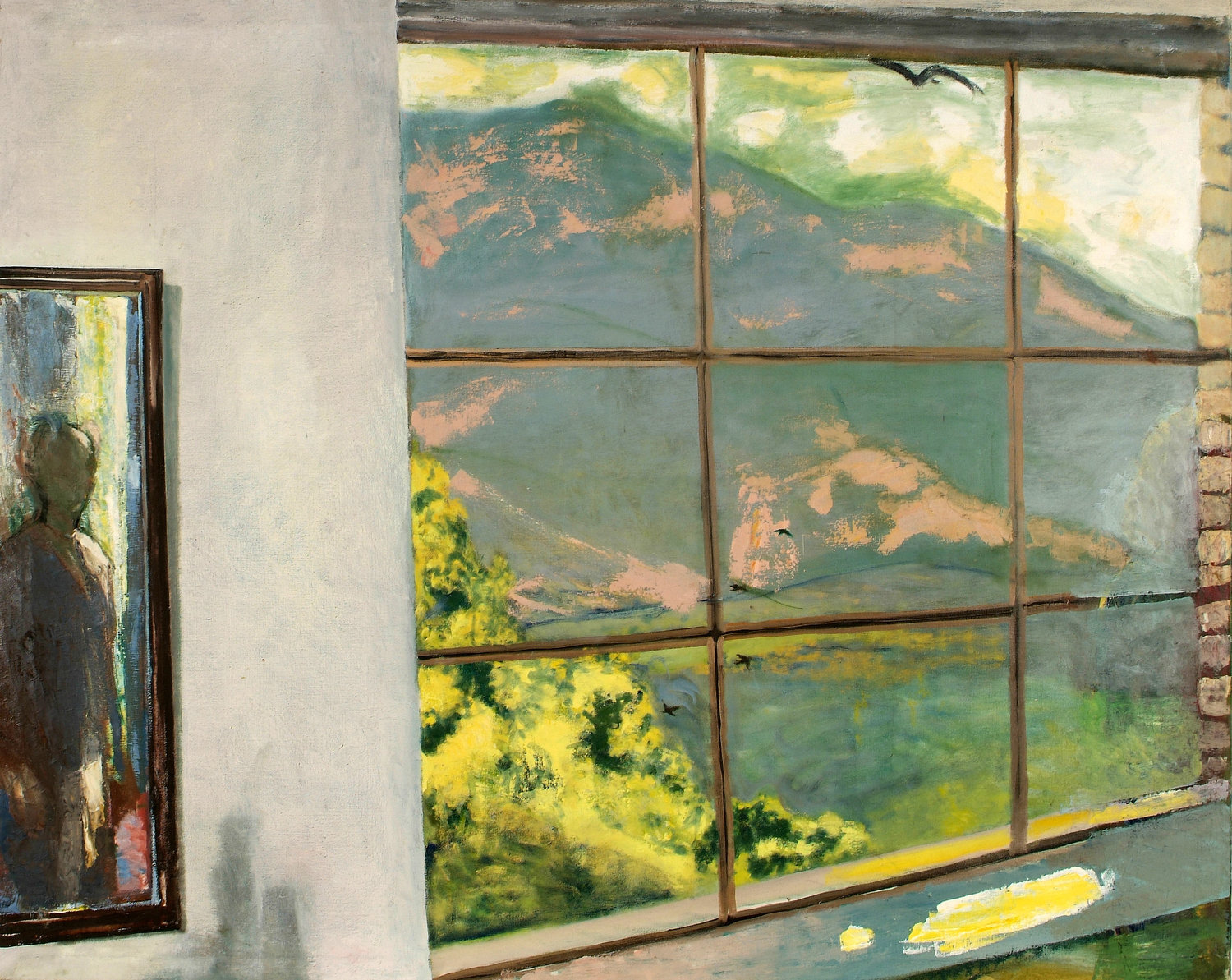

Images used to be treated as opaque or transparent films among experience, perception, and thought. But, now, images are taken to another level, where the viewer is immersed in the image-experience. Burnett argues—though this is hardly a fresh insight—that “interactivity is only possible when images are the raw material used by participants to change if not transform the purpose of their viewing experience” (p. 90). He suggests that a work of art, “does not start its life as an image . . . it gains the status of image when it is placed into a context of viewing and visualization” (p. 90).

With simulations and cyberspace the viewing experience has been changed utterly. Burnett defines simulation as “mapping different realities into images that have an environmental, cultural, and social form” (p. 95). However, the emphasis in Burnett is significant—he suggests that interactivity is not achieved through effects, but as a result of experiences attached to stories. Narrative is not merely the effect of technology—it is as much about awareness as it is about fantasy. Heightened awareness, which is popular culture’s aim at all times, and now available through head-mounted displays (HMD), also involves human emotions and the subtleties of human intuition.

Peer-to-peer communication (P2P), which is arguably the most widely used exchange mode of images today, is the subject of chapter seven. The issue here is whether P2P affects community building or community destruction. Burnett argues that the trope of community can be used to explore the flow of historical events that make up a continuum—from 17th century letter writing to e-mail. In the new media—and Burnett uses the example of popular music which can be sampled, and reedited to create new compositions—the interpretive space is more flexible. Private networks can be set up, and the process of information retrieval (about which Burnett has already expended considerable space in the early chapters) involves a lot more of visualization. P2P networks, as Burnett points out, are about information management. They are about the harmony between machines and humans, and constitute a new ecology of communications.

Burnett’s work is a useful basic primer on the new media. One of the chief attractions here is his clear language, devoid of the jargon of either computer sciences or advanced critical theory. This makes How Images Think an accessible introduction to digital cultures. Burnett explores the impact of the new technologies on not just image-making but on image-effects, and the ways in which images constitute our ecologies of identity, communication, and subject-hood. While some of the sections seem a little too basic (especially where he speaks about the ways in which we constitute an object as an object of art, see above), especially in the wake of reception theory, it still remains a starting point for those interested in cultural studies of the new media. The case Burnett makes out for the transformation of the ways in which we look at images has been strengthened by his attention to the history of this transformation—from photography through television and cinema and now to immersive virtual reality systems. Joseph Koerner (2004) has pointed out that the iconoclasm of early modern Europe actually demonstrates how idolatory was integral to the image-breakers’ core belief. As Koerner puts it, “images never go away . . . they persist and function by being perpetually destroyed” (p. 12).